BROOKLYN, New York, July 3 (By Maria Young for RIA Novosti) – Marina Shytaj clearly remembers the day in 2010 while living in Brooklyn when she learned just how sick she was, news that came in a phone call from her doctor.

“I was cooking, I was holding the phone, and she said, ‘You need to rush to the hospital.’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ She said, ‘You have cancer.’ I thought I was going to drop the phone,” Shytaj recalled, tears streaming down her face.

It was a frightening and shocking diagnosis even though she had been sick off and on since shortly after the catastrophic 1986 accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant about 80 miles (128 km) from her childhood home in Kiev.

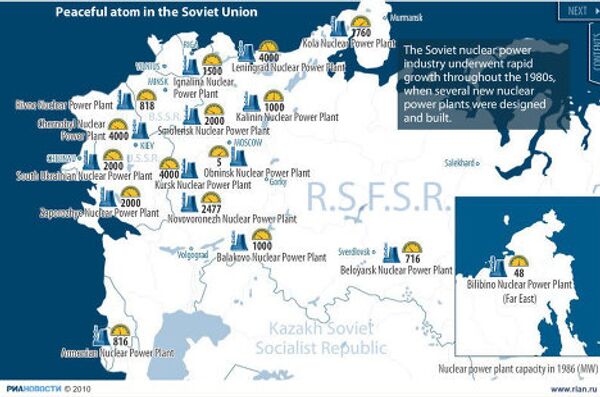

Shytaj, now 30, was just five-years-old when a series of explosions and a fire at the plant released highly radioactive material into the atmosphere, and the dark, ashy fallout spread across Ukraine, Belarus and parts of Russia. Widely considered the worst nuclear accident in history, hundreds of thousands of people were permanently displaced, and scores of others were sickened.

The official death toll was listed as 31. There is some discrepancy about that, and scientists and other health care experts predict the long-term death toll from radiation will be much higher.

Roughly a decade-and-a-half later, Dr. Igor Branovan, a Russian-speaking physician in Brooklyn began to notice an odd trend: scores of Russian immigrants like Marina Shytaj were being diagnosed with thyroid cancer. And many of them – like Shytaj – were surprisingly young.

Yefim Sidel has a similar tale.

He also lived about 80 miles (128 km) from the Chernobyl plant back in 1986, and believes he was exposed to radiation in the weeks after the accident. He immigrated to the United States, and after years of uncertainty about his health, had a biopsy at Branovan’s office three years ago, anxiously waiting the required 40 minutes for the results to come in.

“He did the biopsy, and I came out and asked the clerk, ‘Where’s the liquor store?’ She said it was just around the corner so I went there and took a 750 Hennessy right away,” he said, referring to a heavy dose of cognac.

The results showed cancer cells in his thyroid and lymph nodes. Sidel had surgery to remove the thyroid, and is still in treatment. Shytaj also had surgery and has recovered, but goes through periodic testing and watches her young daughter for any genetic complications.

Both patients feel sure they know where the cancer came from.

“I think it’s definitely from Chernobyl. I talk with my friends in Ukraine and they tell me a lot of people get thyroid cancers. Before Chernobyl this was very rare. And I don’t want to say it’s destroyed my life, but I feel mentally, psychologically, not so well,” Sidel said.

“I think all of the problems I’ve been dealing with, it’s all from exposure to Chernobyl. Before that my mom said I was very healthy, I never got sick,” Shytaj said.

But Branovan, a Russian immigrant himself and one of the only Russian-speaking head and neck surgeons in the New York City area needed more scientific proof.

“You start to ask why. Why are these people getting thyroid cancer? Why should I be seeing so many people from Ukraine or Belarus with thyroid cancer? It just doesn’t make sense,” said Branovan.

He wondered, could there be a link to the accident at Chernobyl?

“Chernobyl for my generation was a pivotal event, sort of like the Kennedy assassination for the previous generation. So even if you weren’t directly affected you still remember when you found out, and the tremendous panic that the whole issue caused,” Branovan said during an interview with RIA Novosti.

The scope of the disaster was magnified, he said, when countries of the Soviet bloc held their annual May Day celebrations just five days later.

“The government, even though they knew there was a huge radioactive cloud hanging over Belarus, the Ukraine and Russia, they still got the people out for the May Day parade. So this increased the radioactive exposure dramatically,” Branovan said.

“And of course there were no iodine pills given, no control over the milk products which is where you get a lot of the exposure. The radiation settles in the grass, the cows eat the grass, they give milk and if you drink milk for the first few weeks you’re going to get a lot of your radioactive iodine that way,” he added.

The thyroid gland is the only gland in the human body that uses iodine, so people who ingest large amounts of radioactive iodine dramatically increase their risk of thyroid cancer, Branovan said. Still, he needed more scientific evidence to make a clear connection between the cases he was seeing and the Chernobyl disaster.

Working with Russian immigrant groups, he began screening thousands of immigrants from two different groups: those who came to the New York area from the Soviet Union in the 70s and 80s before Chernobyl, and those who came after Chernobyl, in the late 80s and 90s. The results were clear and stunning.

“If you take people who lived in Belarus, lived in Ukraine, and really unfortunately were in the open air for the May Day parade, or drank the milk of contaminated cows in the weeks after the disaster, their risk is about double that of the general population,” he said.

Branovan founded Project Chernobyl in 2006, a not-for-profit organization that facilitates diagnosis and treatment of thyroid cancer for victims of the Chernobyl disaster. Since then he has screened thousands of Russian immigrants in the New York area who are considered at high risk for thyroid cancer, and treated dozens whose test results confirmed the disease.

Project Chernobyl is also pushing for testing and eventual approval of minimally invasive thyroid cancer treatments, already being tested on a limited basis in Ukraine and Belarus. Such procedures are much less expensive than the surgical procedures commonly used today, Branovan said.

Last month he led a United Nations conference on applying the lessons of Chernobyl to the aftermath of the March, 2011 nuclear disaster at Japan’s Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant.

Those lessons include:

• Small doses of radiation don’t produce significant health risks

• Larger doses, treated promptly, can be managed successfully

• Screening at-risk populations, rather than general populations, is cost-effective and life-saving

• Pre-positioning iodine pills in the areas close to nuclear power plants can quickly counteract the effects of nuclear iodine exposure

• Equipment should be readily available that can put out a fire in a nuclear reactor or avoid contaminating water supplies without relying on an electricity grid

Another catastrophic nuclear accident in the future, Branovan said, is statistically inevitable.

“There are dozens and dozens of reactors around the world that are sitting in tectonically unstable areas of the world. So when you are suddenly in a situation where you need nuclear energy but an error can create a disaster of global proportions, what do you do? You have to think about things you can do which may not be expensive but which can be effective,” Branovan said. “Nuclear power is an international issue.”

For his patients, the lessons are simpler: be prepared for disaster, get treatment immediately and be willing to help others around the world.

“We cannot control what could happen tomorrow. Only God knows. We could get a bomb tomorrow, but I think basically if it does happen, you take a precaution, you take a pill right away,” said Shytaj.

Added Sidel, “You can’t control it, but you have to be ready for any accident. The world now is not like before. The world is open, we can help anybody but we have to be ready.”