WASHINGTON, March 11 (By Carl Schreck for RIA Novosti) – Texas authorities are sticking to their guns amid complaints from senior officials in Moscow that they have been unable to access investigative materials in the case of a 3-year-old adopted Russian boy who died in Texas in January.

“Right now nothing is going to be released,” Ector County Sheriff Mark Donaldson told RIA Novosti Monday from Odessa, Texas.

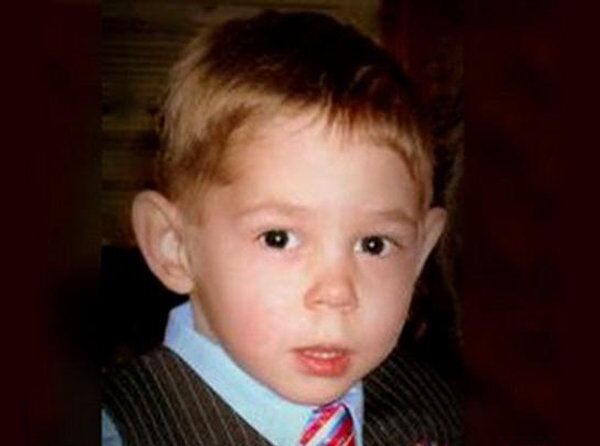

Donaldson’s office is leading the investigation into the Jan. 21 death of Max Shatto—also known by his Russian name, Maxim Kuzmin—who was adopted along with his younger brother by Alan and Laura Shatto of Gardendale, Texas, in November.

Russia’s child rights ombudsman, Pavel Astakhov, has publicly accused the adoptive mother of killing the boy and giving him “psychotropic substances.”

Texas medical examiners have since ruled that he died as the result of an accident, though the investigation into the circumstances of the tragedy is ongoing.

That conclusion that has been met with suspicion in Moscow, where officials complained in recent days that Washington appears to be incapable of helping Russian officials obtain documents related to the investigation, including the autopsy report.

“The US State Department tells us that it can’t obtain the autopsy documents concerning Maxim Kuzmin’s death from Texas authorities. That is strange,” the Russian Foreign Ministry's point man for human rights, Konstantin Dolgov, wrote on his Twitter feed Friday.

Astakhov replied to Dolgov on Twitter the same day, saying it “[i]ndeed seems more than strange.”

“Or has Texas already completely seceded and no longer answers to the federal government?” Astakhov said in a reference to the secessionist sentiment that has deep roots in Texas.

The State Department has repeatedly stated that it can facilitate a dialogue between Russian officials and local investigating authorities, but that it has no power to compel Texas police or prosecutors to hand over documents related to the case.

Donaldson told RIA Novosti on Monday that he was contacted once by Russian consular officials—on March 1, the day the medical examiner’s findings were released—asking for materials related to the investigation.

“We’ve given them the same thing that we’ve given to everybody else,” Donaldson said. “We sent them a copy of the press release.”

Officials in Texas have said the autopsy report would not be released while the investigation is still in progress.

Ector County District Attorney Bobby Bland could not be reached for comment Monday, and the Russian embassy in Washington said officials were not immediately available to comment on Moscow’s efforts to secure access to documents related to the case.

Ambulance workers who arrived at the Shatto home on Jan. 21 found the boy unresponsive and transported him to an area hospital, where he died a short time later.

Bland announced at a March 1 press conference that a report certified by four medical examiners following an autopsy of the boy concluded his death was “accidental” and resulted from trauma “consistent with self-injury.”

Donaldson insisted Monday that investigators still do not know exactly how the boy died.

“We know that he was outside, we know there is a playground out there with a slide and a swing set, … and so a fall from the top of the slide or somehow on the swing set is just one of the many possibilities,” Donaldson said. “There are no facts to nail either one of those down.”

The tragedy has drawn intense international scrutiny, coming on the heels of a diplomatic dust-up between the United States and Russia over human rights and international adoptions.

US President Barack Obama signed the Magnitsky Act into law in December introducing sanctions on Russian officials suspected of human rights abuses. Moscow subsequently banned US citizens from adopting Russian children, a move widely seen as a response to the Magnitsky Act but which Russian officials say is aimed at protecting Russian children from being abused by their adoptive American parents.